That Dragon Cancer

That Dragon Cancer

When game designer Ryan Green and writer Amy Green’s third son, Joel, developed an Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumor (AT/RT) shortly after his first birthday, the Green family was thrown into another world. Ryan decided to tell their story in the form of a game. Using voicemails and messages from the struggle with the disease with a distinctive blank-faced animation style, the game creates a textured representation of their family ordeal.

Why is this game important?

That Dragon, Cancer is an award-winning example of a genre called a “serious game.” A serious game, according to computer scientists from the University of Toulouse, France, is any games whose purpose is not purely entertainment. Traditionally, serious games have been used in education, training, healthcare, and other fields. That Dragon, Cancer, however, falls into the literary/memoir genres (which are not categorized as “entertainment” because… I don’t know why; the same reason “Science Fiction” and “Westerns” are not classified as “Literature & Fiction” I guess).

That Dragon, Cancer has a short play-through and its interactivity is less fully developed than in most commercial console games. The story unfolds in 14 successive chapters. The storyline is tightly controlled and several scenes end with the kinds of forced failures that can feel manipulative in a first-person shooter or adventure games, but which are part of the story and the impact the designer hopes to create. The explorable worlds presented in the scenes include three types of discoveries: the narrative elements are often presented in the character’s own words: a voice message from Amy to Ryan reports her frustration with the lack of a diagnosis or an overwhelming scene where the player points to representations of Amy, Ryan, and two doctors on a child’s See ‘N Say to literally spin out the news that Joel’s cancer has returned, there are no more treatment options, and that the hospital is “very good at end of life care.”

The interactivity is not, as a cynic or skeptic might assume, gratuitous but where used successfully — in my interpretation, anyway — brings to mind Poe’s charge to have a single effect upon the audience. Mixed in with the scenes of anxiety and sadness, there are scenes of bliss that spark hope. Some of the interactivity is pure escapist — like when the player and Joel hijack the red cart used for infant chemotherapy and careen around the hospital floor in a go-cart race. Other moments are smaller, like turning the camera case toward the hospital crib and seeing the 2-year old version of Joel (who the doctor have diagnosed as deaf) bouncing up and down to music,

Is this the best way to tell this story?

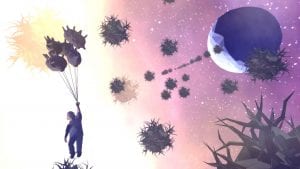

There are “single effect” moments created by the interactivity that would be much more difficult to achieve in other formats; the two most effective are two of the “forced failures.” It is the forced failures that perhaps give the user the greatest insights into what the Greens are trying to communicate about the emotional roller coaster of pediatric cancer.  In the first, Baby Joel is carried away by a bouquet of helium-inflated into space. The user’s task is to avoid the thorny objects that pop the gloves. But this is a forced fail because the only way to move forward is for all the balloons to pop and for Joel to fall.

In the first, Baby Joel is carried away by a bouquet of helium-inflated into space. The user’s task is to avoid the thorny objects that pop the gloves. But this is a forced fail because the only way to move forward is for all the balloons to pop and for Joel to fall.

The other forced fail comes in a scene that looks straight from 1980s era arcade game where Joel heads off to slay the dragon, accompanied by Tim, a young man from the Green’s church that we have learned has already died from cancer. Here again, we know we are fighting a battle that will be lost — we know because Tim is already dead, and doctor after doctor have told us that there is no hope for Joel; and yet, even knowing they will lose, the player is compelled to fight on until their lives are lost.

The drawback of telling even a purposefully designed story in this format is the reliance on functioning technology and a savvy user. I played this on both the PC and through an iPad app. It functioned much more smoothly on the PC, and that was central to the story experience. Late in the game, you are trying to calm Joel and nothing works. At first, I appreciated the unflinching look at what it is to be with a very sick child, but after trying everything in the digital space several times, it seemed clear something was wrong. As I say, at first I thought the single effect the scene was going for was the overwhelming helplessness of not being able to offer any comfort (and I am certain that was the point), but after several more attempts to get out of the scene, I saved my place on the iPad, moved to the computer, and played to the end of the scene successfully. This is not a problem I’ve ever had with a book.

What I learned from this text

As I will doubtlessly write about in a later post, a large percentage of game narratives are based on Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. In part, this is because — as Campbell says — many stories are based on that pattern. However, another major reason for its popularity is that The Hero’s Journey is taught as the formula for a successful story in most film and game programs. That Dragon, Cancer represents an evolution beyond that basic recipe.